"DRAWING ROOM" ALLISON ZUCKERMAN: Brussels

Past exhibition

Press release

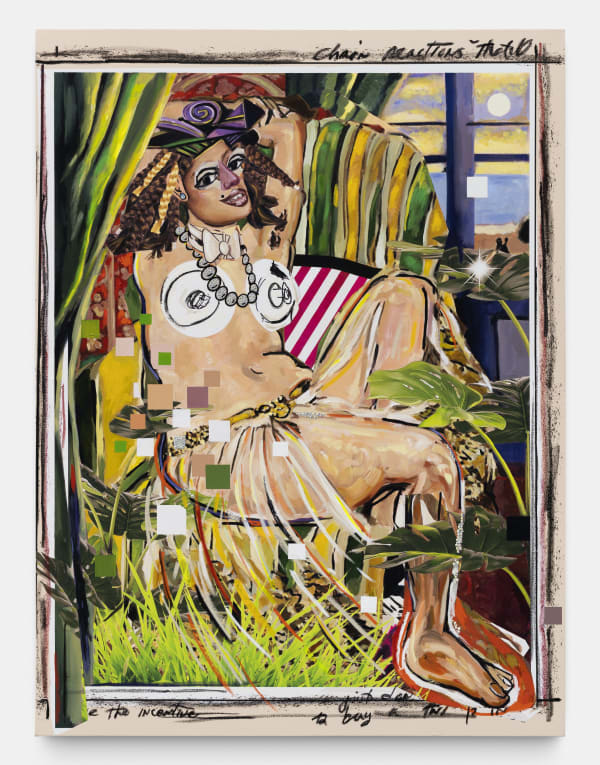

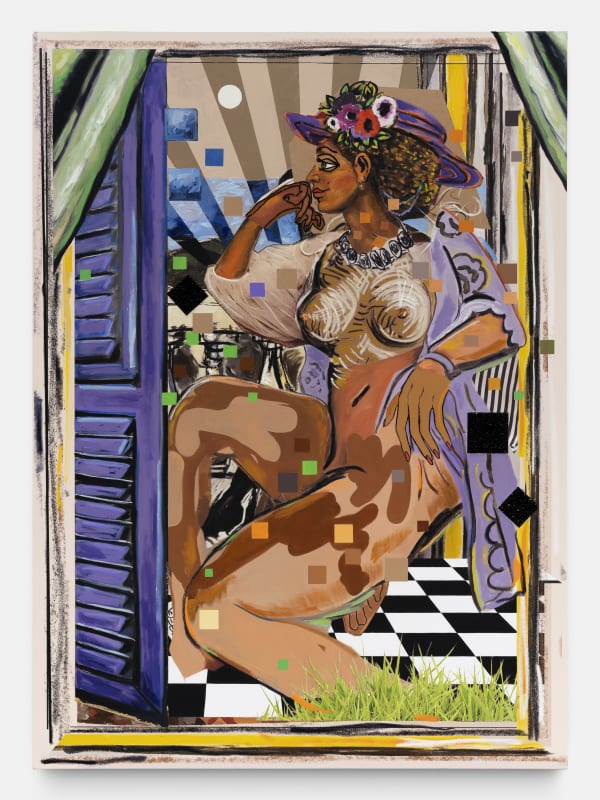

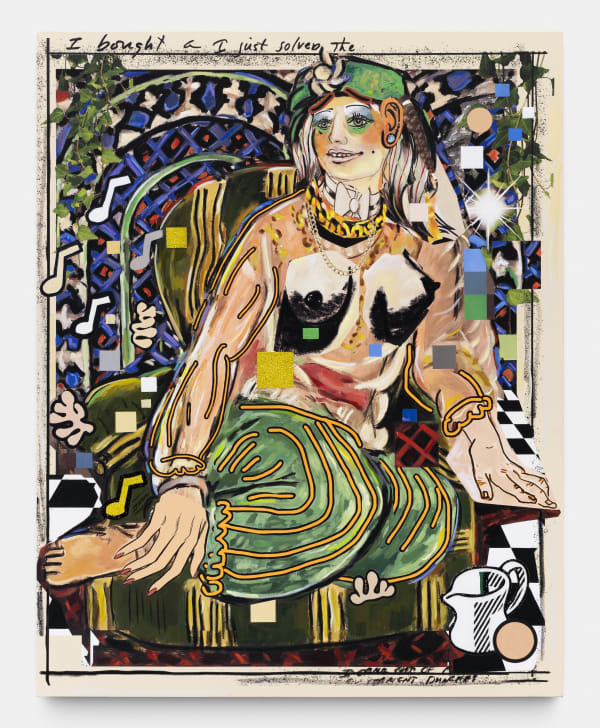

Allison Zuckerman’s paintings, despite their reverence for the art of the past—Matisse, Picasso and Lichtenstein are very visibly sampled—pulse with the frenzied energy of the now. Born in 1990, Zuckerman has synthesized the visual vocabulary of her phone-addled generation with a classical sense of portraiture. “Drawing Room,” an exhibition of 10 new works at Stems Gallery in Brussels is the artist’s European debut. It’s an illuminating new context for work that borrows brazenly from canonical European artists and feeds these sources through a distinctly American consumerist sensibility: More is more and enough is never enough.

Zuckerman deals in optical overwhelm. Her surfaces teem with marks digital and painterly, with rhinestones and pixels, language fragments (here, Richard Prince jokes with no punch lines), and images scrapped and slapped together. The result is an amalgam, the product of a feverish Copy/Paste. ‘Collage’ is a term that has been used to describe Zuckerman’s drawing together of disparate source material, and while it captures the relevant humor and monstrousness of, say, a Surrealist cadavre exquis, it falls short of capturing the frightening dexterity with which Zuckerman moves between realms of pixel and paint, and between registers of high and low.

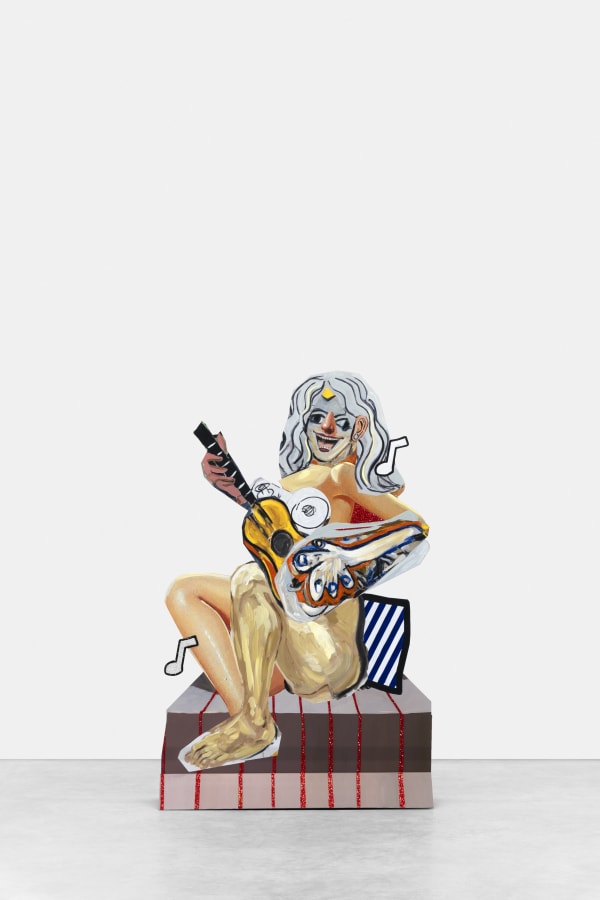

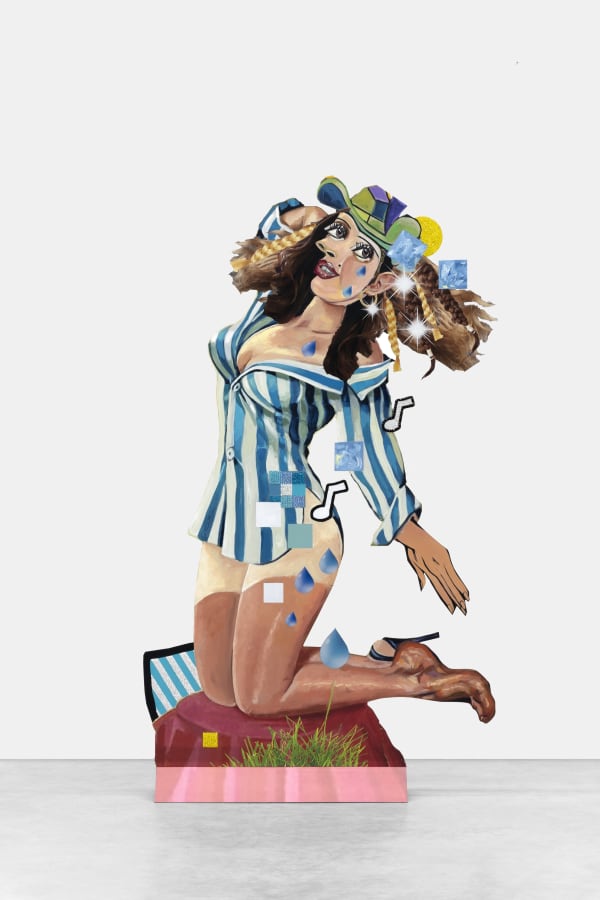

‘Slumbering Through,’ one of two sculptures in an exhibition otherwise dominated by canvases, features a buxom, busty figure on her knees. Her pin-up-y pose, unexpectedly, is derived from Branzino’s mid-sixteenth century painting ‘An Allegory with Venus and Cupid.’ (Many of Zuckerman’s silhouettes recall the lounging grace of great historical paintings.) Preparing for the show, Zuckerman explains that the winking pin-ups of the 40s and the nudie magazines of the 50s (i.e. Playboy) mark the beginning of America’s sustained visual engagement with erotic imagery. Here, the addition of a post-coital men’s oxford shirt and a single sling-back stiletto heel bring this recent history to bear on a figure sourced from a painting circa 1545.

It’s evident that Zuckerman moves confidently through the history of art and her engagement with theory is equally substantial though the work is never weighed down as a result. Take Leo Steinberg’s seminal “The Flatbed Picture Plane” as a frame through which to consider this work. The essay remarks on the flatbed printing press, a relatively novel art-making technology in 1972, highlighting its potential for the endless embedding of material (i.e. Rauschenberg). Steinberg sets up an opposition between work that is upright as reflective of ‘nature’—art as a window or mirror—and work that is produced in a flat orientation as reflective of ‘culture’’—a vessel for recognizable imagery, an indexical surface for all that already exists and circulates in the world.

Using Photoshop as an analogue to the printing press, Zuckerman recalls Rauschenberg and the ‘flatbed impulse’ in her incorporation of printed media and her strategy of image-making by accumulation; the result, though, is legible as a more-or-less traditional portrait. Zuckerman has propped the canvas back up and in so doing swiftly resolved this opposition between ‘nature’ and ‘culture.’ What we’re left with instead is something approaching ‘anti-nature’: Frankenstinian subjects, marvelous and frightening in their distortions and awash in a rush of references from every corner. Each portrait attests to the unrelenting appetite for visual information that is typical of our increasingly digital existence. Returning to the cliche of art as mirror, here Zuckerman holds up a funhouse mirror to all that is unnatural about the way we live.

What is so refreshing about Allison Zuckerman’s treatment of this subject—the convulsive nature of contemporary life—is her smiling complicity in it all. The work does not make recommendations for better living or make moralizing demands. Instead, it revels in glamour and grotesqueness, high art and trash, intelligence and fun. A deliciously dark sense of humor about the world, the work and herself runs through.

Text by Danny Kopel

Installation Views

Works

-

Allison ZuckermanUnexpected Serenade, 2021Oil, Acrylic, Archival CMYK ink, and Rhinestones127 x 84 cm.50 x 33 in.

Allison ZuckermanUnexpected Serenade, 2021Oil, Acrylic, Archival CMYK ink, and Rhinestones127 x 84 cm.50 x 33 in. -

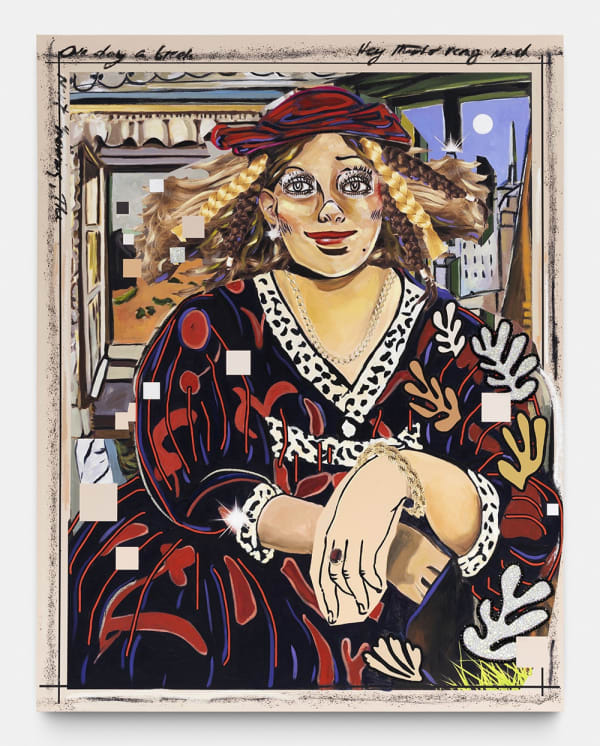

Allison ZuckermanCouncil, 2021Oil, Acrylic, Archival CMYK ink, and Rhinestones158 x 117 cm.62 x 46 in.

Allison ZuckermanCouncil, 2021Oil, Acrylic, Archival CMYK ink, and Rhinestones158 x 117 cm.62 x 46 in. -

Allison ZuckermanPassenger, 2021Oil, Acrylic, Archival CMYK ink, and Rhinestones183 x 137 cm.72 x 54 in.

Allison ZuckermanPassenger, 2021Oil, Acrylic, Archival CMYK ink, and Rhinestones183 x 137 cm.72 x 54 in. -

Allison ZuckermanShuttered, 2021Oil, Acrylic, Archival CMYK ink, and Rhinestones185 x 135 cm.73 x 53 in.

Allison ZuckermanShuttered, 2021Oil, Acrylic, Archival CMYK ink, and Rhinestones185 x 135 cm.73 x 53 in. -

Allison ZuckermanFloored, 2021Oil, Acrylic, Archival CMYK ink, and Rhinestones183 x 145 cm.72 x 57 in.

Allison ZuckermanFloored, 2021Oil, Acrylic, Archival CMYK ink, and Rhinestones183 x 145 cm.72 x 57 in. -

Allison ZuckermanSlumbering Through, 2021Oil, acrylic, and cmyk ink on aluminium and polyethylene109 x 180 cm.43 x 71 in.

Allison ZuckermanSlumbering Through, 2021Oil, acrylic, and cmyk ink on aluminium and polyethylene109 x 180 cm.43 x 71 in. -

Allison ZuckermanStep Wife, 2021Oil, Acrylic, Archival CMYK ink, and Rhinestones160 x 124 cm.63 x 49 in.

Allison ZuckermanStep Wife, 2021Oil, Acrylic, Archival CMYK ink, and Rhinestones160 x 124 cm.63 x 49 in. -

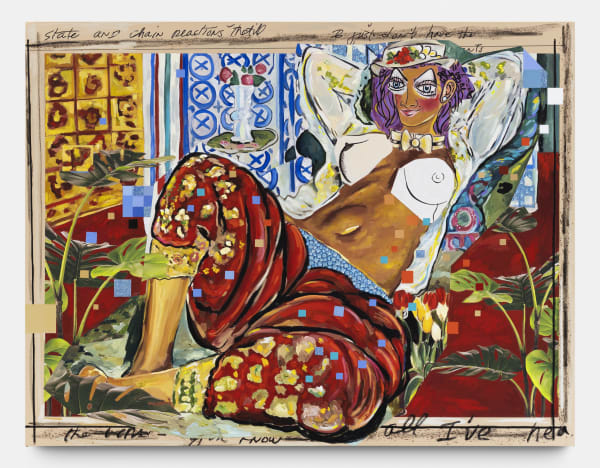

Allison ZuckermanRed Repose, 2021Oil, Acrylic, Archival CMYK ink, and Rhinestones213 x 165 cm.84 x 65 in.

Allison ZuckermanRed Repose, 2021Oil, Acrylic, Archival CMYK ink, and Rhinestones213 x 165 cm.84 x 65 in. -

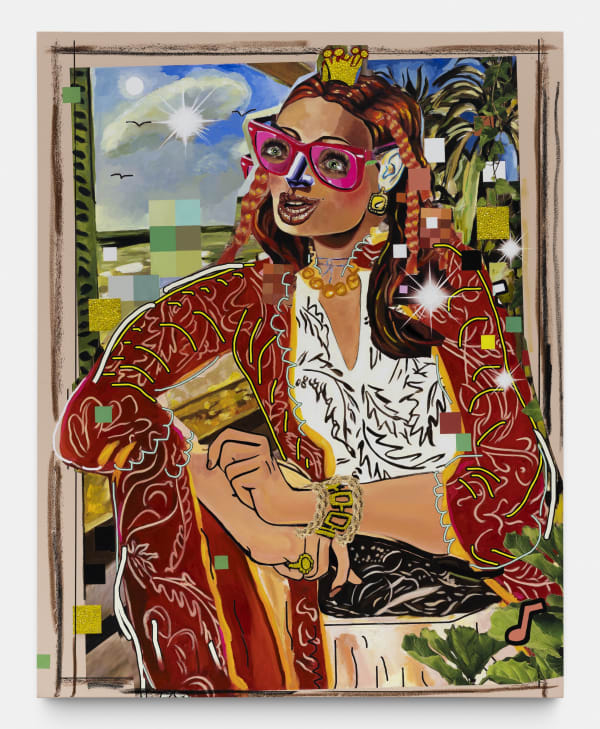

Allison ZuckermanOn Second Thought, 2021Oil, Acrylic, Archival CMYK ink, and Rhinestones157 x 124 cm.62 x 49 in.

Allison ZuckermanOn Second Thought, 2021Oil, Acrylic, Archival CMYK ink, and Rhinestones157 x 124 cm.62 x 49 in. -

Allison ZuckermanSight Reader, 2021Oil, Acrylic, Archival CMYK ink, and Rhinestones178 x 137 cm.70 x 54 in.

Allison ZuckermanSight Reader, 2021Oil, Acrylic, Archival CMYK ink, and Rhinestones178 x 137 cm.70 x 54 in.