LE SOLEIL N'EXISTE PAS - LEO LUCCIONI: Brussels

Past exhibition

Press release

Le Soleil n'existe pas

It is written that the Sun has a mass of 2 x 10³⁰ kg (which is enormous), is composed of 74% hydrogen and 25% helium, has an average diameter of 1,392,684 kilometers, and a surface temperature fluctuating between 3500°C and 5900°C (which is very hot); these are just a few facts about the celestial body that Leo Luccioni would indeed deny if he claimed that the Sun does not exist. It must be said that this would leave even the most fervent flat-earther pale with disbelief, as they too, if they fully followed their ideas, could muster the courage for total negation.

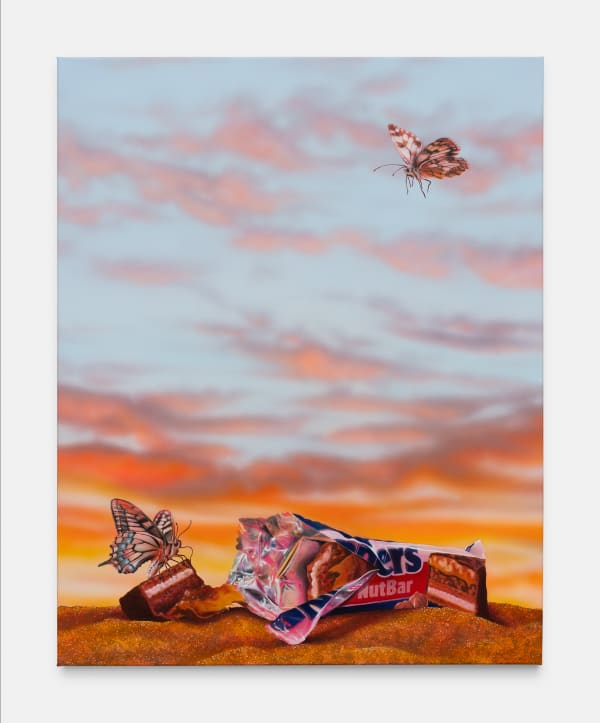

Long before considering the consequences of the catastrophic and hypothetical disappearance of the Sun, the artist attempts, with the Nature morte ? series, an exercise in seduction to which butterflies are the first to succumb, falling under the spell of the sweet yet lush colors of ultra-sugary packaging, which present themselves as the protagonists of the narrative. Once trapped, the monarch butterflies become instruments themselves, drawing the viewer's gaze toward a cocoon of softness and lightness. Perhaps the most ephemeral creatures in our usual landscape, their fragility contrasts starkly with the Sun’s immutability. But to be more precise, one should emphasize that what the artist proposes is not really the disappearance of the Sun, but the suggestion that it simply does not exist—that perhaps it never even existed. While the reddish hues might be explained, in the absence of a sunset, by the imminent possibility of a devastating fire, how, then, does one explain the presence of organisms whose existence is inexorably tied to the Sun? In other words, is this nature truly dead?

Thus, these gentle-toned paintings are not merely a cynical aestheticization of a vividly colored globalization but a condensation, an almost obsessive collection of the contradictory signs of a fire that could just as easily be a sunlit paradise. In the background, a more or less abstract landscape casts doubt on the source of its light. The beach, where the aesthetically pleasing packaging lies, is mirrored by the island depicted in the painting Coucher de soleil. This incandescent painting seems to confirm the dystopian direction of the narrative, offering a globalized perspective on the unfolding catastrophe.

To paint these landscapes, Leo Luccioni notably uses an airbrush. A tool favored by graphic designers and advertisers in the 1970s, the airbrush played a crucial role in the evolution of commercial imagery. Truly democratized through hyperrealism, it allows for the application of paint without contact with the canvas, casting doubt on the pictorial origin of the image. Among the artists who have used it, one could mention Don Eddy, Audrey Flack, Ben Schonzeit, or even Guerrino Boatto.

If the subtle reference to clamor-filled capitalism is made through the use of this tool associated with advertising, the commodity-like subjects in the paintings explicitly underscore the overconsumption of industrialized and ultra-processed products. More than a mere display or showcase, the artist, now a "pictopublicophile" (a term for a collector of advertising images derived from the Latin pictus, meaning "painted"), experiments scientifically with his precious objects through all the senses: each element is carefully handled, smelled, photographed, and tasted before being reproduced. But this reproduction, the translation from object to image, is perhaps less a transformation of nature than an emphasis on the role these flashy objects play as desire-enhancers before our eyes and in our hands. Without its shiny packaging, a Cheetos might be just a heap of stinking powder, and the Bubble’n’roll, a mere tasteless softness without the entertainment of its carefully shaped tongue, which invites a butterfly to linger there. In this way, it is no longer the edible item that is chewed, but the gum (is it not, after all, what erases?) that threatens to engulf the delicate creature.

With Snack de frappe, Leo Luccioni invites the public to awaken from their intimate contemplations with a striking jolt of reviviscence. Where González-Torres invited the spectator to take sweets, Leo Luccioni incites blasphemy and the consensual violence of objects whose raison d’être is to receive blows. True functional punching bags and a nod to the exhibition site’s failed future, these leather prints question the value of packaging, sometimes exalted as they are on supermarket shelves or in Nature morte?, sometimes thrown under our feet or transformed into targets for our fists. This sudden altercation shakes the sugary poetry of the butterflies and proposes an alternative to the gentle interaction between work and spectator. However, craftsmanship here contrasts with function, opposing disregarded objects with the luxury of high-end leather goods.

Without ever venturing into moral judgment but rather elevating the investigation to a genealogical study of a light oscillating between the artificial and the organic, Leo Luccioni expresses with Le soleil n’existe pas the only percentage missing from the mass of the star: its supposed negation.

Jeanne Mouffe

Installation Views

Works

Video